#14 GOOD GRIEF NEWS

Zooming in on End-Of-Life Care and why it deserves more imagination

Museum Küppersmühle Duisburg / Herzog & de Meuron, picture by Simon Menges

Last month, I attended the LEBEN UND TOD (Life and Death) conference in Bremen, Germany – a unique gathering that brings together hospice workers, palliative care specialists, grief counselors, chaplains, and people simply seeking to understand the end of life better.

Even as someone deeply engaged in death trends and farewell culture, I left the conference with new insights and once again the question: Why is this final phase of life usually so underrepresented? Why doesn't end-of-life care receive more recognition and attention?

Yes, death doulas are more prominent nowadays and care influencers are educating us about this area on social media. However, this is more of a sideline discussion.

But not only do we live longer these days, we also die longer. The final phase of life is being extended by medical advances and better living conditions, which is why we should think more about it.

Photo series “Red River” by Photographer Meghan Marin, portraying her grandmother’s battle with lung cancer (via The School of Death, Berlin)

Why we avoid this conversation.

We’re often more concerned with what comes after death than with how the final phase actually unfolds. It’s striking how much more openly we now discuss funerals and grief rituals. But public discourse rarely touches on the end-of-life phase, which is often spent in frailty at home or in care institutions, nor does it address the support and environments that people truly need when their physical abilities diminish and perhaps they become fully dependent.

I've taken part in several “death meditations” – exercises in imagining your own final days. It’s always revealing how many people picture themselves lucid, mobile, and able to choose when and how to go. A deeply human desire that I understand. But realistically, for many of us, the end may involve confusion, fatigue, pain, or dependency. Few are prepared for that.

One reason for this is our problematic relationship with ageing. In health circles, we increasingly talk about the health-span rather than the life-span, focusing on how long we live in good health. However, what happens after the health span ends remains a blind spot. Once people can no longer actively participate, they tend to disappear from public view – and often from our imagination too.

Ageing is still viewed negatively in our society. Being bed-bound or dependent on others is deeply stigmatized, often associated with shame, fear, or loss of dignity. We imagine this final stage as a period of suffering. But could it still be a time of joy?

Dying has become institutionalised, professionalised and medicalised, and is often removed from the family setting. Studies consistently show that most people would prefer to die at home, yet only a small proportion actually do so. The general narrative is dominated by curative medicine rather than palliative care. Most of us don't grow up with the experience of caring for someone through this process. This unfamiliarity makes it more difficult to confront it and more challenging to envision what meaningful support could look like during this phase.

Image via Aurore Brard

Designing for dignity: Future-proof memories

I was particularly satisfied with the newly created 'Startup Campus' at the LEBEN UND TOD fair in Bremen, as it showcased two projects dedicated to this phase of life that took into account the needs of patients, their families and their caregivers.

The first one is Future-Proof Memories by Dutch designer Aurore Brard. Her work explores a powerful question: How can design still reach us when language, memory, or orientation begin to fade?

Brard develops intuitive tools that support people with Alzheimer’s and dementia, helping them feel safe, seen, and connected, even in vulnerable moments. Her approach draws on familiar gestures from daily life, like cooking, walking, or washing dishes – activities deeply anchored in muscle memory and emotional meaning.

The result? Playful, tactile objects that stimulate the senses and evoke curiosity; designed not just to soothe, but to spark autonomy, connection, and dignity. These aren’t just products. They are invitations to care differently, reminding us that good design can touch people when words no longer do.

Images via finally. Design

For more quality of life in fragile times: finally.

Also featured at the Startup Campus was finally., a Zurich-based label that stands for a new design mindset in care – one that centers dignity, empathy, and aesthetics in some of life’s most fragile moments. Founded by Prof. Bitten Stetter (ZHdK), finally. makes visible what is often overlooked: vulnerability, illness, and decline – not as failures, but as part of life.

The brand develops thoughtful, beautifully crafted products for people in caregiving contexts. From hospital gowns that resemble dresses to ergonomic ceramic cups that double as discreet assistive tools, these are not just functional objects, they affirm the person using them.

More than that, they open up new possibilities for caregivers too, creating spaces of closeness, presence, and shared dignity, rather than merely facilitating care routines. In a time when efficiency and automation dominate conversations in the care sector, finally. offers a different perspective: one that bridges the gap between technical care and human connection.

It’s a design practice that doesn’t shy away from frailty, but meets it with beauty, clarity, and intention.

Images from the Friluftssykehuset Outdoor Care Retreat in Oslo

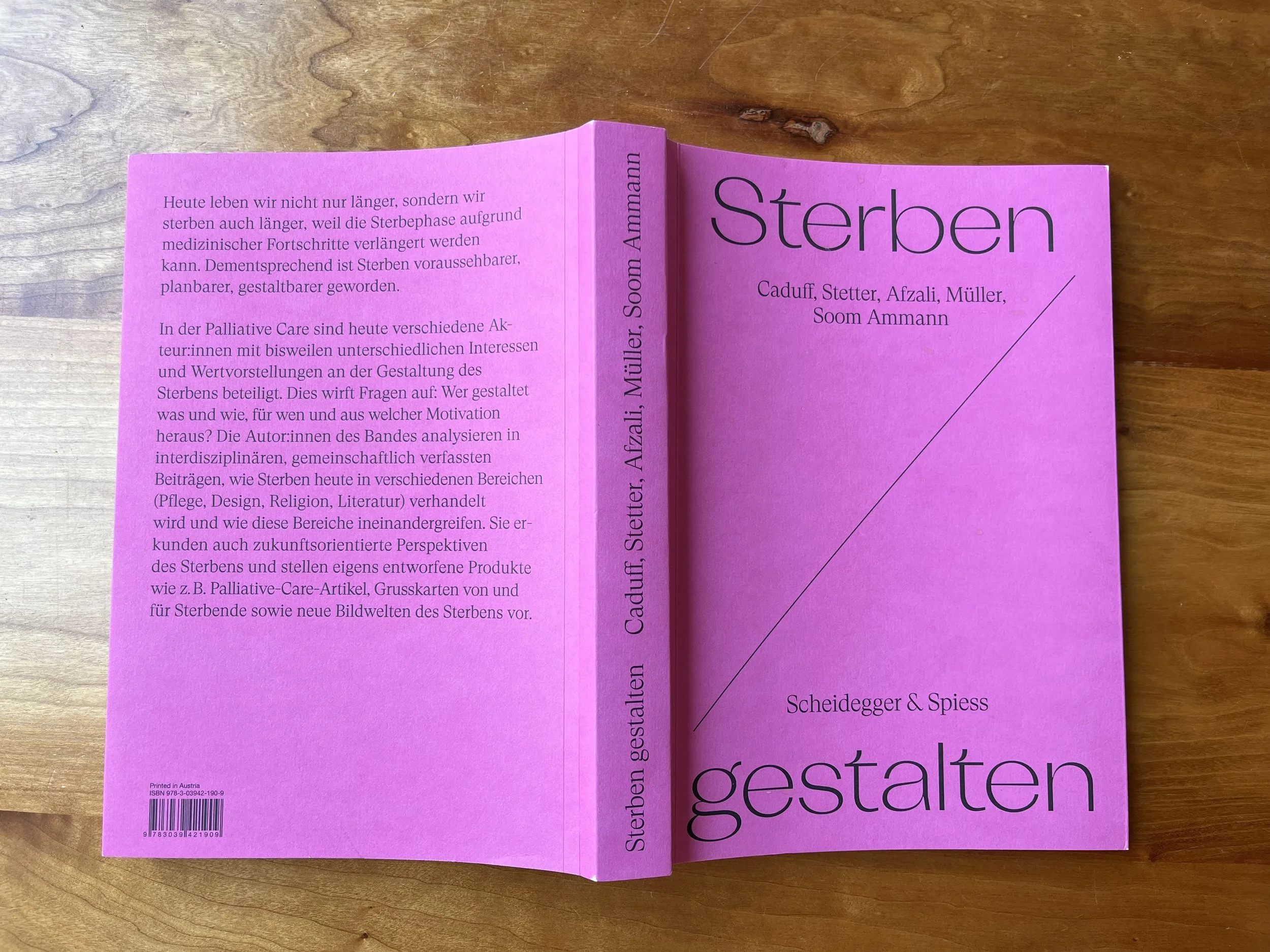

📚 Book Tip: “Sterben Gestalten”

Shaping Dying – Spaces of Possibilities at the End of Life

by Corina Caduff, Bitten Stetter, Minou Afzali, Francis Müller, Eva Soom Ammann

This book presents the findings of the interdisciplinary research project, ‘Settings of Dying’ (2020–2023), a collaboration between the Bern University of Applied Sciences and the Zurich University of the Arts.

The contributions in this book present various perspectives and results of the project, which I found inspiring and which broadened my perspective on the topic. The authors analyse possibilities emerging from everyday palliative care practice, examine gender differences and explore future visions of dying. The volume concludes with new proposals for product design and visual communication.

Currently, the book is only available in German.

Cover of the book “Sterben Gestalten”, Scheidegger & Spiess, own image

🎟️ Event Tip: End Well 2025

If you're curious to dive deeper into the future of end-of-life care and hear from some of the thought leaders in the field, here’s my personal recommendation: End Well.

It’s an amazing global conference on this topic—and it’s happening again on November 20th in Los Angeles.

End Well is not your typical industry event. “End Well is a nonprofit on a mission to make the end of life part of life.” It brings together designers, clinicians, caregivers, technologists, artists, and advocates—people who are all reimagining what the end of life could and should feel like. Expect big ideas, intimate stories, and real talk about care, grief, mortality, and meaning.

If LA feels too far, no worries: they always offer livestream tickets, so you can join the conversation from wherever you are.

I’ve found past editions incredibly inspiring—and surprisingly energizing. Highly recommended.

End Well conference audience, taken from their website

Thanks for reading!

> Interested in working with me?

Get in touch if you would like to request a trend talk or inspiration session, or if you are interested in consulting work in this area. Alternatively, you can also book a Pick My Brain Call if you would like to discuss your personal project / startup and need more strategic input.

***

> GOOD GRIEF NEWS, is a monthly newsletter on trends and fresh perspectives around death, grief and remembrance. You can see more of my work at goodgrief.me or stefanieschillmoeller.com and feel free to follow me on Instagram.

06.06.2025