#16 GOOD GRIEF NEWS

On Communal or Community-Led Death Care: An Interview with Staci Bu Shea

In recent years, a growing number of people have begun to reimagine how we die, how we mourn, and how we care for our dead – not as a private, clinical event handled exclusively by professionals, but as a deeply social, relational process embedded in community. This shift is part of a broader movement toward ‘communal death care’, which emphasizes the active participation of family, friends, and neighbors in end-of-life care, after-death rituals, and grief support. Rooted in practices that predate modern funeral industries, communal death care seeks to reclaim death as something we do together, not something done to us or for us.

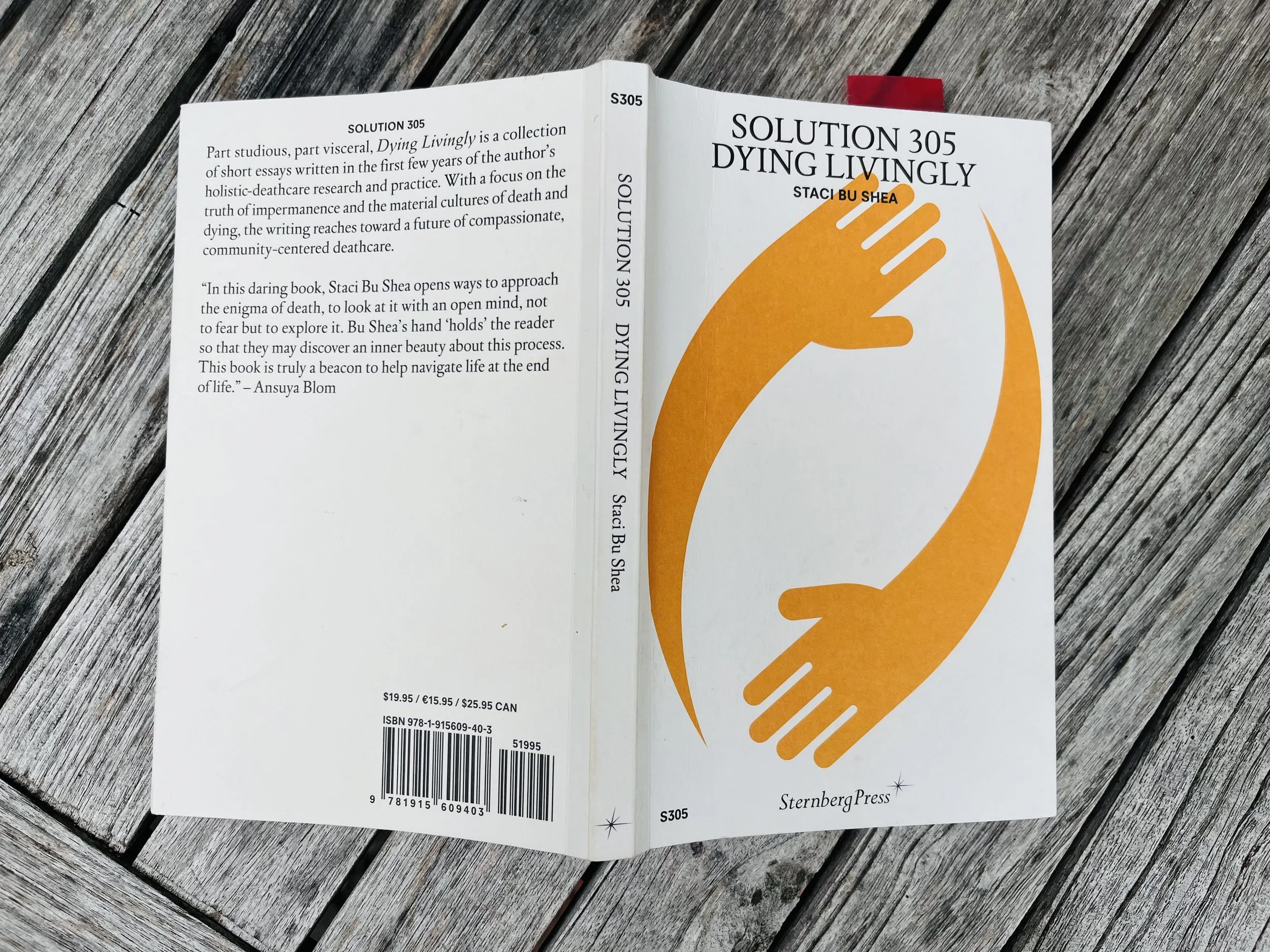

This month’s interview with Staci Bu Shea, author of Dying Livingly, sits powerfully within that context. Their work as a holistic deathcare practitioner, curator, and cultural worker reframes death not as a clinical event to be managed, but as a relational, spiritual, and deeply political process: one that touches every part of our lives, from the intimate to the systemic.

I want to be honest: this conversation isn’t light. It’s layered, complex, and at times confronting. But it’s also very stimulating. Staci's reflections speak to many of the questions we have about care, value, mortality, and collective healing, especially at a time when death often feels both hyper-visible and emotionally unattainable.

Whether you work in end-of-life care, advocate for justice, or are simply curious about how we might live more intentionally in the face of impermanence, I hope this interview will offer both resonance and challenge.

So make yourself a cup of tea, take your time, and step into this conversation about death, care, and everything tender in between.

Photo by Ieva Maslinskaitė, courtesy of Page Not Found

💬 Interview with Staci Bu Shea: Dying Livingly

A few weeks ago, I joined the launch of Staci’s new book Dying Livingly at Page Not Found in The Hague, and left with my notebook full and my mind spinning. I reached out to continue the conversation, and they generously agreed.

To begin: In Dying Livingly, you guide us through your path into holistic deathcare. For those new to the term, what does holistic deathcare mean to you? And how does it differ from what we might think of as ‘conventional’ or ‘medical’ death work?

SB: Thank you for engaging with the book and initiating this interview, Stefanie. It's really wonderful to be in touch with you through our shared commitment to this work.

"Holistic" comes from holism, the theory that parts of a whole are in intimate interconnection. So, a holistic approach in care addresses someone's health or quality of life (also the wellness of a community or environment) in a comprehensive way through the different components that help to shape it. Take for example the experience of pain. The biopsychosocial model of pain reminds us that pain is not just happening in one, isolated area but all three realms: the body, mind, and relational environment. A biomedical view would focus on physical sensation and medication, whereas a holistic one would consider emotional, cognitive, and behavioral factors as well as social support, cultural beliefs, and socioeconomic realities, all of which could be interacted with for pain relief.

We can extend this model to consider our relationship to grief, the pain associated with loss, which also transforms with and can be interacted from across multiple domains. Psychologist Mary Francis O'Connor writes in The Grieving Body that "dying of a broken heart" is not simply a metaphor but a real phenomenon because the stress of acute grief brings increased risk of heart failure. To think of the physiological effect of grief is not to make it more medical but to emphasize the systemic, holistic interplay of our lives. Then we can understand how grief is a health disparity, and imagine how communities who experience a lot of violent death are at greater risk themselves simply from the sheer magnitude of this stress and pain.

Communal and spiritual care, meaningful connection through ritual, and adaptive practices of repair become medicine to help us process the loss in our lives. Holistic care is a perspective or attitude that makes more space for the body to include familial, societal, ethical, and spiritual influences from which practices, techniques and methods are inspired. This may sound abstract, but it involves self-awareness and considering the micro and macro-levels of our thoughts and actions and what kind of effect they have. From this orientation we have the ability to engage with our lives by having a hand in our own experiencing.

Approaching deathcare in this way shines a light on the dynamic realities of death and dying, and offers more possibility to co-shape it in meaningful ways. To meet death, as hospice nurse Barbara Karnes has advocated since the early 1990s, not as a medical event but an emotional, spiritual, and communal one. Holistic deathcare honors the wholeness of someone, and involves empowerment through knowledge and more agency in decision-making. Consider the care that happens to a loved one's body after death – people can be involved in that space to help slow down time and say a last goodbye. Or the choices for what happens to your body after you die – there are more ecological and mindful options. But of course, all of this means learning and having conversations about death and dying within your life, not only at the end of it, which means facing death. Developing death wellness, let alone awareness, is a feral endeavor yet has power to soften you for the better if you allow it. That's why it can take a lifetime to figure it out. Life and death are both messy and imperfect – the goal is to reduce the chance of harm. Caregiving and receiving, too, while complex and challenging in their own vulnerable ways, has the potential to become in depth and evocative, intimate and transformative.

The holistic deathcare movement broadly reaches to the desires and needs of the before-during-after spaces of death and invites our intention. Conventional or medical death work features outsourced care and organization with less family and community involvement, default religious funeral practices, usually with templated and thus uninspired rituals, and more focus on symptom management and living as long as possible – fighting against death. It can feel reactive, rushed, and chaotic. I don't think this is any individual's fault, but an effect of larger cultures of death phobia and avoidance. Holistic deathcare is where science, culture, activism, and spirituality meet; where we chaplain ourselves and each other through change and what the truth of mortality has to teach us when we bring it back into our hands and communities. Death doulas, in their varying expressions and practices of presence, compassion, and attentiveness, are a central figure in this.

Death is currently still seen as a private event. But I agree, more and more, I hear people talking about community-led or collective death care. Why do you think this idea resonates so strongly right now, especially in our individualistic culture?

SB: Depending on our experiences and where we live and come from, we have very different connections with death, meaning as communities we have diverse perspectives on what it means to live, to survive generations, to be in relationship with ancestors and the unseen. Death, like life, is both personal and political, and how we interpret that depends on our place in the current polycrisis and systems, where we struggle and alongside whom. Some deaths are not private at all: instead we watch them on our newsfeed, filmed from other people's phones, from police body cameras. We have to continue to find ways to witness and participate but not numb out, so we say or write their names as spells for their dignity and raise our voices for their lives.

We are witnessing episodes of State-sanctioned mass death, violent and calculated like what we see in Palestine, and when we flip the channel we watch choreographed death in movies and other media, and we are moved by nonfictional stories of death and grief that touch us through art and literature. We are inundated by death, both real and staged. At the same time, expected or sudden personal losses are directly altering us and our communities in real time. When it's brought close to home, when we are brought to the edge of y/our mortality, the profound weight is immense and we're not resourced enough to wade through it alone.

I don't think we ever have been, but the discrepancy is unavoidable now. At large we lack cultures and material conditions that empower us with knowledge and support in death and grief. We are exposed to so much death and yet we have so little collective, common arenas in which death is part of our lives in intentional, revered ways. There is a disbalance many of us seek to level out and an irony to abandon: disregard for death creates a devaluing of life. Decades of dwindling welfare and divestment in public infrastructure in favor of neoliberal capitalism has intensified our experiences of alienation, isolation, powerlessness, and meaninglessness. It takes a lot of effort to unlearn the privatized self, for its both imaginative and real. I think the ways in which we feel let down in end-of-life spaces or in response to our grief, even while everyone tries their best, is directly connected to these other larger, systemic forces that disenfranchise us. Many of us crave connection in a felt, shared sense, and want to leave the loneliness of individualism in favor of collective power, especially over our care for each other and for those the capitalist medical system is not interested in caring for.

In any case, care and healing is a collaboration. Its event can feel like an experimental symphony of many diverse and stunning voices and instruments. No matter what, people will keep finding ways to care against all odds, but only through collective liberation will we be able to experience the extent of how transformative our care can be.

You also imagine a future where deathcare is rooted in shared spaces. In the book, you write about “death commons” – places like integrative care centers and grief houses. Could you share a bit more about that vision? What might these spaces offer that our current systems don’t?

SB: While we live more and more digital lives, I believe that the creation of such brick-in-mortar places will become an antidote to our need for collective ritual and care as well as hands-on practice for responding to personal and collective death and grief. Death commons, localized, specific sites could enliven the dynamism around death and dying and give deathcare more contemplation, sensuous qualities and organization. They would be religious in the original meaning of the word, which is thought to be related to either "religare" (to bind, connect) or "relegere" (to go over again, ponder, or consider carefully).

While focused on death and grief care, death commons are interdisciplinary in how people are brought together, how they participate and learn, as well as sustained through diverse economies: hybrid mix of public, private, and community support. For example, as of now, you don't go to a hospice unless you have to or are someone who feels the call to witness death and dying. Imagine for yourself what it would mean for hospice to be much more part of life, what it might feel like if your local hospice also included a garden, an artist residency, and community center and you wanted to be there. Maybe it could function as a membership program, and the same place where you care for the dying could also be where you die too. There would be a lot of life in these places where the basics of maintenance, cooking, cleaning, attending, presence, become elevated, more thorough and beautiful. The strength would be in how these different forms intertwine to support engagement with death, dying, loss, and grief. It's vital we imagine different structures and systems to generate energy around the future we want.

While so much about this movement is around education and literacy, the focus on end-of-life spaces – the care that we can help shape because of the gift of time – becomes a very tangible and empowering way to engage with death awareness and wellness. We owe so much to the hospice movement of the past half century that sought to bring more attention to and around the dying and we build off of its intentions. Once hospice became part of health insurance in the US in 1985, this was an incredible step for affordability and accessibility of this care. But hospice as we know it now is part of the medical model, with a lot of focus on management of symptoms related to illness or disease than with preparation for the sacred event that is dying, death, and grief. In that structure, there often isn't the time and money to provide death education, support, and guidance in a conscientious way. People and communities need more information and knowledge before they reach the front door. We must meet people where they're at, but also work on our communication and outreach. We’re entering into a new period where non-medical dying spaces are emerging in people's homes or other coordinated-care housing projects. These are commonly known as social model hospice homes, comfort care homes, and homes for the dying. Medical care teams are still part of this process but non-medical parts of care get more space and reflect the spirit of the people and culture of the local community. Examples of this emergent practice in the US include the Center for Conscious Living and Dying in Asheville, NC; Asphodel House facilitated by A Sacred Passing through the A Place to Die program in Seattle, WA; and The Grief House in Portland, OR. Integrative and interdisciplinary death commons would be a next step from here.

In the book, Grace's Hospice is fictional but is inspired by the architectural drawings of my friend Grace Caiazza who conceptualized an end-of-life space in their interior architecture studies. I wanted to build out through text what could be a 4D rendering of that space. The design supports the dying and their loved ones to encounter themselves and each other through its experimental architecture. I think there's a lot that is possible here, but in the end, as I share in the book, interior spaces will always be adapted and reclaimed, however small of a gesture, to meet the desires and needs of the dying and their loved ones.

At the same time, I'm interested in how deathcare spaces can support us to find more ways to close the distance between supposed "good" and "bad" deaths so that we are more equipped and resourced to respond to the times we are living. Less about judgement, more about a unification of the personal and political realities we face.

I’ve found in many of my group workshops and talks, people have a real difficulty talking about end-of-life care at a time of livestreamed genocide in the same breath. The necropolitical scene of genocide via colonial occupation or the austerity of destiny-of-death by covid narrative and reality for vulnerable populations are both examples of "deaths pulled from the future," a turn of phrase I learned from the podcast Death Panel. The reality of these bad deaths fuel our activism.

Palliative Care (with a capital P and C), like many other institutions in both the US and The Netherlands where I'm most familiar, have been awfully silent about political situations which are clearly death-dealing atrocities of utter destruction. When we recognize that these realities are not separate but are distinct and nuanced, we can build more connections between what is life affirming and sustaining and participate in the work of repair and healing. I really appreciate how Dr Yasmin Gunaratnam, author of The Death of the Migrant, has talked about how we can expand our terminology: what Palestinians are experiencing in Gaza is a situation of palliative care. This extends to Ukraine, Sudan, and the Congo, where people struggle to care for their lives while dominant powers grab resources and extract wealth.

Photo by Ieva Maslinskaitė, courtesy of Page Not Found

I wanted to ask you something that feels both personal and structural. In Dying Livingly, there’s a clear critique of how deathcare gets commercialized and folded into profit-driven systems. On one hand, I agree, it feels deeply uncomfortable to see care exploited or turned into a luxury. On the other hand, many of those doing this work are trained, committed, and still often expected to offer their time for free – especially as women. Do you think there’s a way to hold both truths? To challenge extractive systems and advocate for care work to be valued and paid accordingly?

SB: Our task is to figure out how to hold both of these truths with awareness of what we can learn, influence, and change. In some ways I think that the antidote is in the poison: care work must be valued accordingly within our current late/end stage capitalist economy. If it were, capitalism as we know it now would not be able to continue if we properly valued care work for what it is, essential and at times invaluable, incommensurable. Our care institutions are rooted in slavery and colonialism too, so racialized, gendered labor as well as ableist tinkering with what it means to be human is the inheritance we have to deal with. Matters of life and death are never neutral because oppression and violence shape who has access to wealth and power. Having a tuned-in, accessible deathcare practice would mean considering all of this for our clients and community, finding ways to work the system but also think out of the box.

In terms of the commercial death industry, I'm most critical of the products and services which seem to me to prey off of our fear and anxiety, offering a bandaid or quick-fix like death is a problem to solve or the pain of grief is something that should be eliminated. Forgive me for I'm not tech savvy, but AI of our dead loved one could perhaps be a useful grieving tool for a period of time, but not without our investment in the deeper spiritual work or care necessary in the life-changing event of death and all the adaptation and wisdom it invites. The simplest things are always best, like slowing down and getting quiet in order to process grief and learn through loss. But like care, this lacks sparkle at first until the hard labor of grief, the kind we never ask for but must do, bears some fruit.

There are basic needs that the market can't sort out on its own in equitable ways, like housing, food, education, culture, and care. So many can't afford care in the US because the out of pocket burden is too great, so to me social insurance models like here the Netherlands are essential. The booming elder population and need for more caregivers is such an impending reality of fiscal pressure to contend with. With working-age population stagnating, I read one estimate that warned by 2060 over 36% of Dutch workers would have to be in health and long-term care just to meet demand. Informal care is still the backbone of care, and there's a shift back to home and community in many places because it's just too expensive. Death doulas and social model hospice care is born at precipice of all this.

So, the key issue of how care is valued, how we are going to care for each other, and how we will define that cost. We will be able to sense it in a deep way when care is valued. We will feel more supported and will be less burn out. I don't have any idea of perfection but I do believe in the individual and the collective capacity to transform. I think flourishing cultures of care and solidarity across class and cultures will be what builds lasting change. Since care is a necessary part of life no matter what as we will all be caregivers at some point in our lives, Universal Basic Income would be another viable answer.

You come from an art background and now work in deathcare. Some might think of these as very different worlds, but for you they clearly connect. How do your curatorial or artistic practices shape the way you approach death and care?

SB: Both art and care are necessary aspects to maintaining a life, and whether we call it by these names or not, it's still influencing and informing every aspect of life from ideology to institutions, interpersonal relations to internalized ones. To create and to care are very natural aspects of survival and it's a more-than-human quality. I'm invested in what it means and entails to build sensitivity in both art and care to inform our skillfulness in how we connect with each other, our daily lives, and greater environment. I'm interested in how we make sense of our lives and relationships and the means we choose to express what matters. At the heart of these converging life/work practices lies my commitment to cultivating aesthesia (the capacity for feeling) that helps us turn toward the truth of life and death to honor what we love and what brings us meaning, through and because of both our joy and pain.

Let’s talk about the title: Dying Livingly. You write that “deathcare becomes a revolutionary form of life care.” What does it mean to die livingly and why was this phrase the right one to hold the book?

SB: Another way to elaborate on what I shared above, beginning a deathcare practice can help exercise and thus strengthen our sensitivity toward what we value, where fear and anxiety around death and grief become invitations toward compassion and connection. The title is meant to emphasize what it means to give attention in and around the dying and hold that as priority first and foremost, a methodology for approaching life and what it means to live. However painful, I think we must accept our reality with all of its immensity. Only then can we envision more ways we could be loved and cared for in our lives.

There are two extraordinary figures who give image and feeling to dying livingly, the late poet and activist Andrea Gibson and ecoactivist, Buddhist and systems theorist Joanna Macy. They both made an indelible impact on many lives and continued to contribute to their loved ones and community all the way through their death. They held a wild love for life, and life continues to generate from their dying. They specifically turned towards death with curiosity. The two understood that control is an illusion, death is not something to battle, and our greatest power is our relationality, which is always living beyond us. They were intentional, as were their circles of care who held the space of their dying. These two special people have died in the last month. But one doesn't have to live a public life to die livingly, there are plenty lives who still hum in the hearts of others for what they gifted in their life and on their way out. Death is a great teacher but so are the dying and their carers. We are always learning how to live and die from each other.

In the book, you describe a beautiful exercise: writing a letter to Death. Could you share a short prompt or set of instructions for readers who might want to try this? What have you noticed this kind of writing opens up for people?

SB: The practice of writing, whether using epistolary, narrative or experimental methods, is so beneficial for a contemplative, spiritual practice. I learned of death journaling from doula Francesca Lynn Arnoldy as way to share one's changing relationship to mortality awareness as well as a living legacy object. I often suggest this practice with my clients and continuously observe how this form has helped us hold a steady death contemplation as our lives change. Every now and then, as my perception and relationship with death evolves, I write a letter to Death herself in my journal. I borrow and adapt this exercise from death doula Diane Button, and find it supports people to sync their words with the energy that comes from their thoughts/feelings about death to reflect how they are living their life. Through approaching death directly, it's possible to reveal to yourself the ideologies, scripts, and deeper fears and anxieties that you have about death.

With a seven month old who is starting the gradual cognitive development of object permanence, I've been writing to Death about this particular period where Joan floats in a sea of experience, who doesn't differentiate herself from others, and doesn't yet comprehend that objects are still there even when they disappear. Post-birth, I'm having a spike in death anxiety and I am preparing for the learning curve of continued separation and reunion from this beautiful new love that I have. I find it incredible we spend our lives transforming through attachments, both seen and unseen. So, inspired by this current state, I'd like to invite the reader to write to Death on the topic of place. Consider the place we come from before birth and where we go after death as a harbor. A place of coming and going where land and water meet, a safe holding for return. Flesh out the details of this environment. What does your harbor look and feel like? Share what it means to you and ask for advice from Death.

Thank you so much for the interview, Staci!

Thanks for reading!

> Thanks for reading GOOD GRIEF NEWS, a monthly newsletter on trends and fresh perspectives around death, grief and remembrance. You can see more of my work at goodgrief.me or stefanieschillmoeller.com and feel free to follow me on Instagram.

> Interested in working with me?

Get in touch if you would like to request a trend talk or inspiration session, or if you are interested in consulting work in this area. Alternatively, you can also book a Pick My Brain Call if you would like to discuss your personal project / startup and need more strategic input.

07.08.2025