#19 GOOD GRIEF NEWS

A NEW ERA OF DIGITAL GRIEF: hyper-real, meme-ready resurrections and what they do to mourning

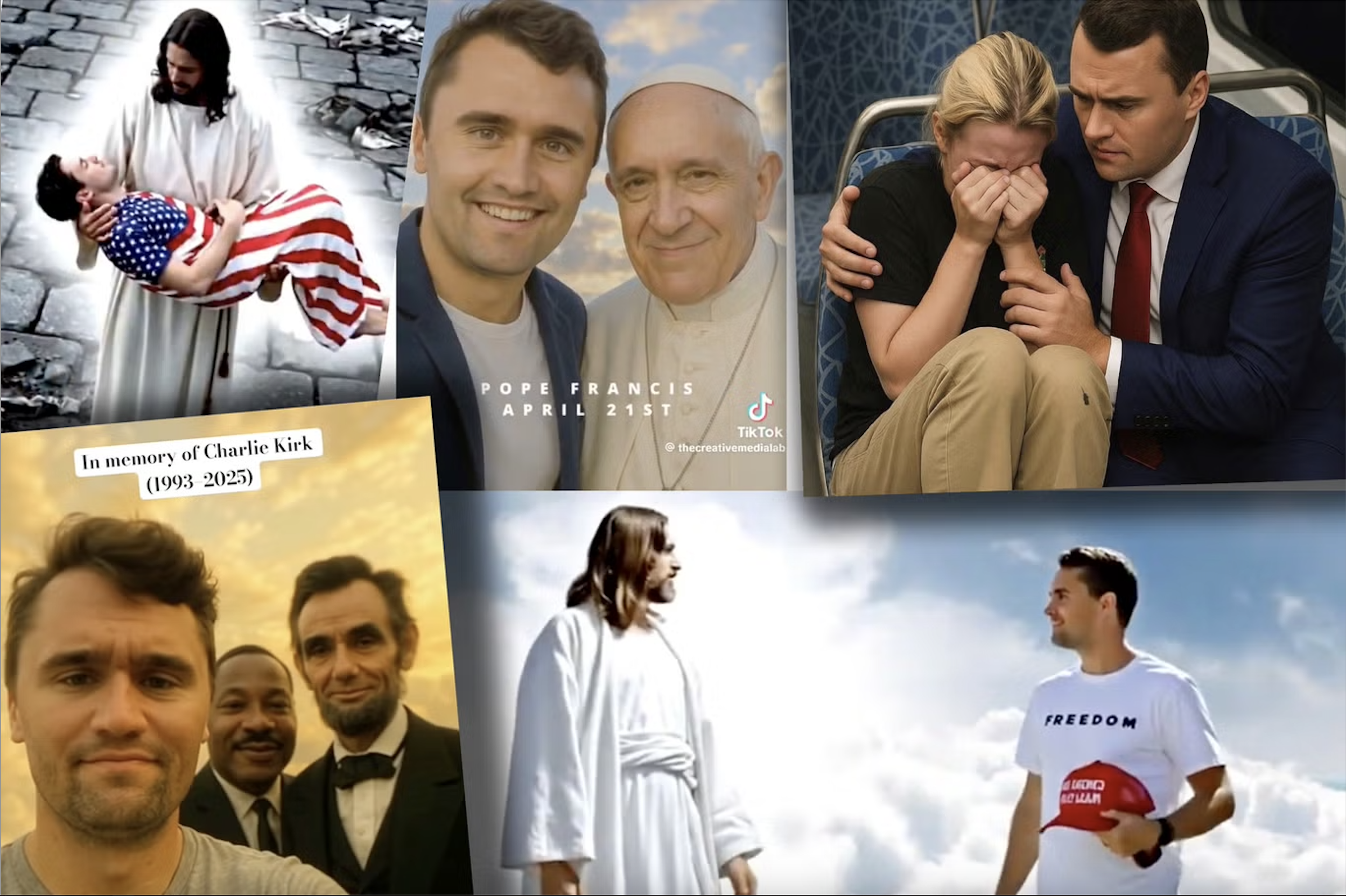

AI-generated content of Charlie Kirk found on social media. (RNS illustration)

The question of what happens to our digital selves after we die has been on my mind since I started tracking death-culture trends in 2019. A recent event made me think about this topic again: The AI-generated speech and social media content that have been circulated following the death of right-wing political activist Charlie Kirk. The reason: It shows that we are no longer simply or merely using digital technologies, and AI in particular, to provide comfort to the bereaved with animated memories and realistic chatbots.

The next step is that AI allows us to create dazzling, hyperreal afterlives: fast, shareable, meme-friendly versions of the deceased that are completely fabricated and no longer even attempt to be realistic in any way.

The case of Charlie Kirk has caused the situation to escalate from disturbing to alarming. After his murder and around the time of his funeral, an AI-generated recording of Charlie Kirk’s voice was played for thousands of congregants at some of the largest churches in the US. The clip, framed as ‘words from beyond’, urged mourners to “pick up their cross and get back into the fight.”

The ‘Kirk clone video’ spread quickly: it was played in churches, posted on feeds, applauded by listeners who knew the audio was synthetic yet were moved anyway. Around the same time, feeds filled with images and videos that put Kirk into imaginary scenes: selfies in heaven, awkward encounters with celebrities, or sentimental reunions with victims he’d commented on in life. The result: a wave of hyperreal public mourning that felt less like remembering and more like staging.

From grief bots to carnival-style resurrections

We’ve seen experiments with digital afterlives for a while: chatbots trained on a deceased person’s messages, avatars stitched from old photos, or memorial feeds that bring together a lifetime of posts. While these projects were ethically challenging, they mostly attempted to remain faithful to the original person, albeit imperfectly. The new phenomenon is different: it’s intentionally playful, sensational, and fleeting. It’s memes dressed as memorials.

This change is important. Previously, post-death technologies were presented as a way to provide consolation by enabling people to keep a memory of a loved one close. Now, however, these tools are being used to fabricate alternative scenarios, remix reputations and embed fictitious events in the public consciousness. Where once the goal was plausibility, now the goal is virality.

Meme-ification is not innocent

Why does this spread? Because emotionally charged and surprising content is shared more widely (Polarization Loop Model). We share things that shock, comfort or amuse, and AI makes it easy to produce images and clips that evoke all three emotions. The result is a flood of 'tributes' that appear more or less credible because they feature a familiar face and voice.

This flood also changes how meaning is created. AI-generated speech can be sampled, clipped and repackaged as prayers, political messaging or comedy. Fabricated content can be woven into the cultural record and amplified by repetition in a matter of hours. Repetition breeds belief: the more we see something, the more real it seems. On a hyper-tailored social feed, the same synthetic clip can reappear repeatedly until it becomes basically ingrained in our memory as something that has or could have happened.

But there’s a second shift happening too: it’s not just that repeated exposure makes the fake seem real. People increasingly know it’s synthetic and yet they still accept it. In a media landscape where everything can be remixed and the truth is negotiable, authenticity becomes less important than emotional resonance. If a fabricated version feels more comforting, satisfying or aligned with our worldview, it becomes the preferred reality. This is not a failure to detect the fake, but a cultural willingness to embrace the version that 'works better'. It’s a cultural surrender to the hyperreal.

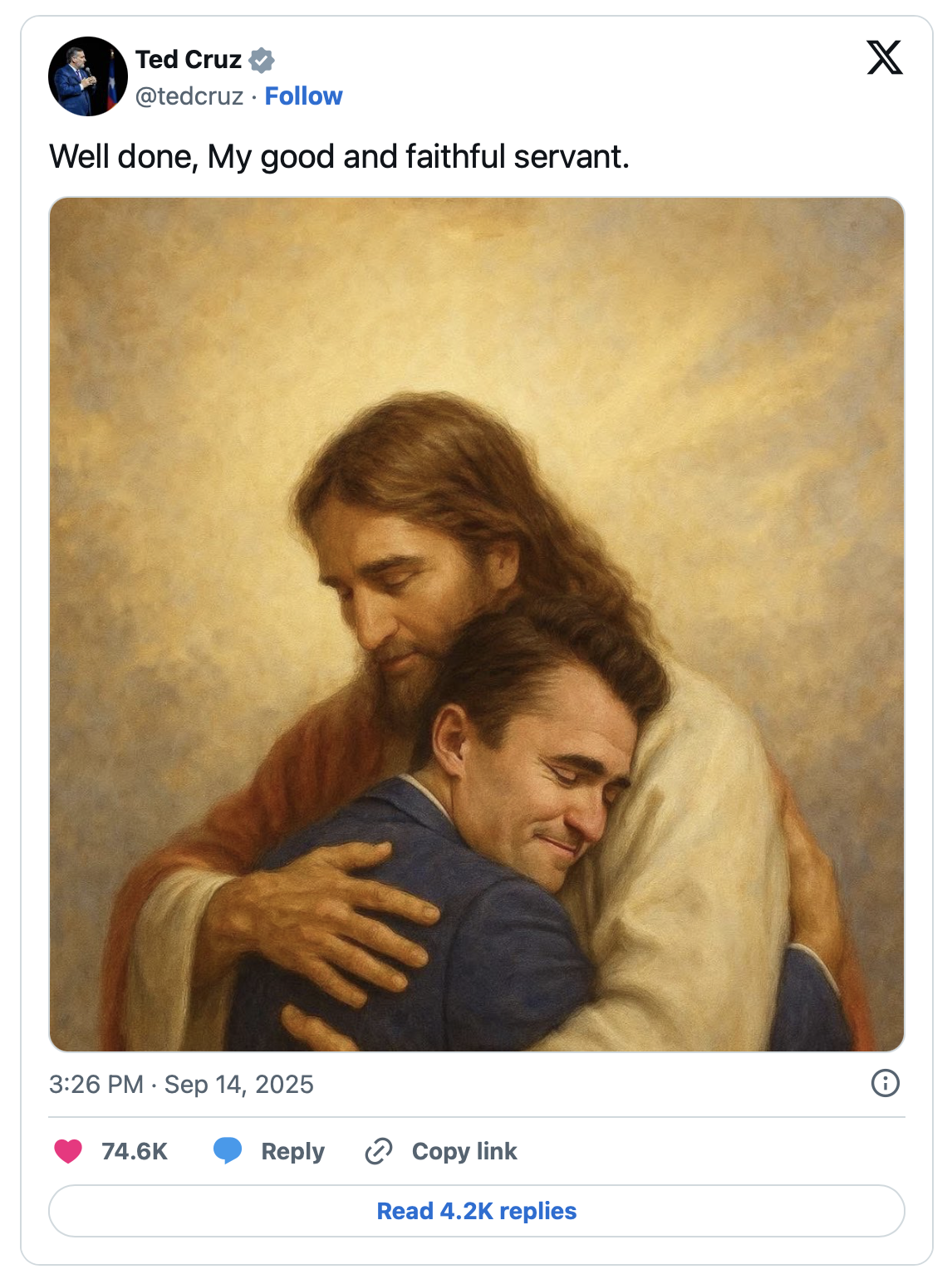

Screenshot of a Ted Cruz post on X

When politics meets synthetic grief

The problematic aspect isn’t tasteless celebrity comedy, it’s persuasion. Synthetic voice clones and avatars can be used to broadcast endorsements, sermons or political calls to action in a deceased person’s voice. That’s propaganda dressed as remembrance. It’s frighteningly easy to imagine a future in which ‘from-beyond’ endorsements become a tactic to influence voters or amplify false narratives. “Once upon a time, it was the families left behind by victims that would provide the first-person narratives, and now the victims themselves are campaigning on tragedies that killed them.” (Elaine Kasket)

What does it do to mourners?

As always, I guess there is no simple answer. For some, an AI clip can be cathartic, offering a chance to hear a loved one's voice again and somehow feel a human connection. For others, however, it is grotesque, an invasion that distorts the person they knew. Everyone experiences cognitive dissonance: we know rationally that the audio or image is fabricated, yet our bodies react as though it were real.

This dissonance deserves attention. Rituals such as graves, wakes and repeated storytelling impose friction. They demand time, care and community in the grieving process. They transform memory into a slow, social practice. By contrast, AI's instant-replay model is frictionless by design: you just need to click and consume. While there is comfort in immediacy, there is also loss. When mourning becomes an on-demand feed, the slow process of forming and retaining meaning through ritual risk being eroded.

AI-generated images of Ozzy Osbourne and other deceased music icons taking selfies together in Heaven shown at a recent Rod Stewart concert in North Carolina (Source)

A cultural test case: when memorial becomes meme

The Kirk example is instructive because it combines all the ingredients: politics, vocal supporters that share information quickly, and a cultural ecosystem that is comfortable with spectacle. However, we have seen similar dynamics elsewhere: AI-revived pop stars performing again, AI voice clones being used in ads, or celebrity ‘appearances’ created for shock value. The common thread is the increasingly blurred line between tribute and product, homage and content.

Last thought: will we trade weight for immediacy?

We already live in an attention economy that rewards immediacy. Technology now gives us the false impression that we can tidy up our digital legacy, smoothing over the difficult aspects of grief. I worry that we’re at risk of replacing the weight of memory – the quiet, inconvenient actions that make grief real and shared – with instant performance.

To prevent mourning from becoming mere content, we must act: set consent as the cultural norm, demand transparency and responsibility from platforms and recognise the value of the challenges of remembrance. Otherwise, it won't just be deceased celebrities that we're remixing; it'll be the meaning of loss itself.

💬 Interview

When I thought about this topic, there was really only one person I wanted to interview: Dr. Elaine Kasket. I read her book All the Ghosts in the Machine in 2019 and listened to a podcast interview with her about the 'Kardashian hologram', which sparked my fascination with the topic of digital death and afterlives. I feel honoured and very grateful that I had the opportunity to ask her a few questions and share her responses with you!

Dr. Elaine Kasket is a cyberpsychologist, writer, keynote speaker and Visiting Professor at the Centre for Death and Society at the University of Bath. She is a leading expert on the digital afterlife, digital grief, identity and the ethics of data after death.

Dr. Elaine Kasket – Photo by Nicolas Laborie

1. What were your first thoughts when you saw the AI-generated speech of Charlie Kirk and the response to it?

My first thoughts were how this connects to some previous examples, including the Israeli domestic violence PSA from 2021 and the Joaquin Oliver interview from earlier this year. In both of those instances, AI recreations were used to try to effect regulatory and social change around difficult social problems such as domestic violence and gun violence -- specific issues. The Charlie Kirk example feels like an expansion of this - taking someone who was already a guru/a revered figure, positioning him explicitly as a martyr/saint, and turning his persona (and all that he represented in like) into a kind of holy/unassailable figure. The explicit sanctification imagery of an already-powerful figure, extending his influence after death and making opposition to him something akin to blasphemy, is something quite different to the use of 'ordinary people' to make a point about the issues that killed them.

2. Some people frame AI revivals as creative tributes. From your perspective, where does creativity end and harm begin?

Yes, the 'creative tribute' argument was made in various circles about the Ozzy Osbourne memorial, which featured imagery not dissimilar to the one of Charlie Kirk with the pope. Kanye certainly had a bit of fun with the Robert Kardashian hologram that he gifted to Kim. The hologram tours are presented as entertainment/fun tribute, although of course they're a massive cash cow for the estates of those dead pop stars and the hologram companies who own them and are sending them out touring.

I have a lot of thoughts about all of these, including the cultural stagnation that the latter represent. The real harm, in my view, comes with what you identify in the newsletter - the Ministry of Truth angle, extending 'freedom of speech' argument not just to one's own speech but to the speech you might choose to place in the persona of someone else, all against the backdrop of an environment where it's becoming increasingly hard/impossible to distinguish fact from fiction, creation from the historical archive. In this context I think there's an increasingly strong argument for its being illegal to deepfake anyone, including the dead.

3. You’ve been writing about griefbots for years. Do you see this moment (synthetic resurrections at scale) as the beginning of a new phase in digital mourning? (Why not?)

It had better not fucking be. I am completely opposed to technological solutionism for non-problems (including the non-problem of normal human loss and finitude), especially when these phenomena are being driven by the exploitative and extractive forces of the market, to line the pockets of the companies that sell us these technologies; when those selfsame technologies contribute to the rapid desiccation of the planet, destruction of our ecosystem, and extraction of its resources; and the creeping normalisation of thinking about any aversive experience as a pathology or problem to be designed out, resulting in rapidly increasing psychological brittleness.

4. Do you think we need a new cultural vocabulary for death in the digital age? I sometimes wonder if we’re trying to force old grief models onto new technological realities.

A lot of grief models were (very helpfully, as many weren't evidence based) on their way out when the Internet arrived to resurrect and reinforce them (see the summary of my book chapter with Dr Morna O'Connor here). So in a way I really wish that the WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industralised, Rich, Democratic) assumptions about mourning and grief that are encoded into today's algorithms would be undermined and challenged more than they are currently being.

But yes - I think we need new vocabularies that correspond with new understandings of posthumous rights, more appropriate to posthumously persistent data that is redolent of the person and which is vulnerable to exploitation. I'd be in favour of do-not-bot-me rights for everyone (not just celebrities), without this having to be arranged pre-death.

Jim Acosta interviews an AI-generated Joaquin Oliver, who was killed seven years ago. Photograph: Screenshot Youtube

5. It often feels like personal identity is becoming impossible to protect and that platforms have little incentive to safeguard it. Where do you see realistic responsibility lying now: with tech companies, lawmakers, or individuals themselves?

Platforms have zero incentives to safeguard personal identity. They're only interested in your personal identity as far as they want as much of it as they can get to monetise. No one is holding tech companies responsible or accountable, and they're in bed with an increasingly authoritarian American government. Bruno Giussani's recent monograph (in French), Moins d'Amérique dans nos vies, underscored to me what a problem this is. We're naive to expect them to adhere of their own volition to charters or guidance. Regulation is the only way forward, but this can't be forced either, as we're seeing. Right now I'm focusing on controlling what I can control, which is very little, and using my voice to try to be an influence.

6. If you could advise people on just one thing when it comes to protecting their digital legacy, what would it be?

You can't.

Once, deletion of data on social media and in other accounts upon a user's death was the default. Now, memorialisation and retention are the defaults, so this data is available. Everyone could eventually become a griefbot. As part of your legacy, you could bequeath not just your assets and wisdom but also your apparent 'presence' to future generations. But is that really worth the costs?

My advice is, don't doubt the influence and impact you have on future generations. You contain layers of intergenerational legacy yourself. The influence of your predecessors is with you in so many ways. I think the best legacy I could give to future generations is to get out of the way. I do not want to be drinking the water of the living or taking their work or cramping their style by 'sticking around.' I do not want to contribute to ideological or cultural stagnation. I do not want my legacy to be misrepresented through deep fakes.

So, I know I won't be able to completely control this. I could be easily deepfaked. I'll make my wishes to be known. But I don't know whether the law will support me in ensuring those wishes will be observed.

Thank you very much for the very interesting interview and your thoughts on the subject!

👉 I’m curious:

What do you think about AI-generated memorials and digital resurrections? Have you come across examples that moved or disturbed you? Have you tried out such memorials yourself? Hit reply and share your thoughts!

💡 And if you’d like to dive deeper into future-ready rituals, deathcare innovation, or cultural shifts around grief and remembrance, I also work with organizations or startups on strategic foresight, innovation projects, and keynote talks. you can also book a Pick My Brain Call if you would like to discuss your personal project and need more strategic / trend input. Let’s chat!

Thanks for reading!

> Thanks for reading GOOD GRIEF NEWS, a monthly newsletter on trends and fresh perspectives around death, grief and remembrance. You can see more of my work at goodgrief.me or stefanieschillmoeller.com and feel free to follow me on Instagram.

02.11.2025